Democratic Global Governance with UN Reforms: Toward the Future Multipolar World 通过联合国改革实现全球民主治理: 面向未来的多极世界

12月号封面文章

面向未来的多极世界

By [Sweden] Jan Oberg, PhD, director, The Transnational Foundation for Peace And Future Research, TFF, Lund, Sweden

文| [瑞典]扬·奥伯格(Jan Oberg) 瑞典隆德跨国和平与未来研究基金会创始人、主任

导读

●导言——为什么科学必须关注可能的和更美好的未来

● 民主

● 联合国改革与全球治理

“There are those that look at things the way they are, and ask why? I dream of things that never were, and ask why not?”

George Bernard Shaw (1856~1950)

Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist, Nobel Literature Prize laureate 1925.

Introduction – Why science must focus on possible and better futures

This is written in Sweden, in a Europe where the risk of war—most likely a conventional war between NATO and Russia—has increased markedly. We live in a time characterised by failure to solve humanity’s most urgent, existential problems, such as reducing poverty and militarism and stopping what is euphemistically called climate change, i.e. global environmental warming and rampant destruction of our environment.

Thus, it can be argued that, measured on essential criteria, the global system is approaching limits beyond which there will be no return. In an extreme scenario, the use of nuclear weapons would imply both omnicide (of human beings) and ecocide (of Nature).

It is, therefore, no wonder that many people turn a blind eye to reality, delve into entertainment, focus on their identity and appearance, and go about their “near” everyday activities feeling helpless or depressed at what they watch on the news (if they have not dropped the news completely).

While psychologically very understandable, this is devastating for every type of democracy and for the prospects of saving the world or, at least, changing it somewhat for the better.

However, this reaction of hopelessness and resignation – resigning from the larger dimensions of humanity into the culture of “me,” the world of play and games, pleasurable escapist activities, etc. – is exactly where society’s power players would like their citizens to be. Elites can make decisions to their own benefit more easily if their citizenry has given up engaging in society and the larger world.

I don’t want to sound moralistic, but in my view, this is not a choice for an intellectual or a genuinely devoted change-maker. I would argue that it’s a professional duty to use the imagination and outline constructive “futures” and strategies to realise them, put them out for debate and avoid both criticism-only and defeatism.

There are various reasons behind this standpoint.

A peace researcher must be inspired by Gandhi’s Constructive Program and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Beloved Community – that is, the necessity of constructive thinking – or, as it is often phrased: plant a tree even if the world may end tomorrow – or, light a candle rather than curse the darkness.

Changing the world, big or small, cannot be fuelled by only empirical knowledge of what is wrong or critiquing what’s being done wrongly.

It can only be the result of constructive thinking, of a vision – of something we work for and not only by working against something.

The pioneer of peace and future studies, Johan Galtung (1930~2024 and one of my mentors) saw this as an integral part of the scientific investigation. Thus, what we do in social science in general and peace and future studies in particular is an interplay between three things – Data, Theory and Values, thus:

The classical—but limited—science process involves developing hypotheses about how the world works, testing them using consistent methods, and concluding what can be said about the world with reliability and validity. This is the main paradigm of natural science, but it is woefully insufficient for social science.

George Bernard Shaw: “There are those that look at things the way they are, and ask why?”

In social science, we must acknowledge that we are investigating something that we ourselves are, in a fundamental sense, part of. That means being very aware of our values and how they influence our interpretations.

There is no perfectly objective truth possible – objectivity is nothing but inter-/ or multi-subjectivity: Something can be confirmed with the same quality methods employed by a number of scientists who come to the same conclusion about how the world works. If just one comes to another result with the same methodology, the theory cannot be confirmed. But it can still be discussed and lead to new, refining research.

This is where the similarities between peace research and another goal-oriented science, medicine, become clear.

A good doctor makes a knowledge- and experience-based diagnosis but does not leave the patient with a prognosis to the effect that the patient will soon be dead. An absolutely essential element in medicine is to answer the fundamental question: Given what we know, what can be done to create health and prevent a fallback to the disease? That is treatment or therapy vis-a-vis the individual, and – in a similar manner – peace and future research produces exactly that type of future thinking, visions – simply new concepts and good ideas – at a higher level: How to create a better world and devise scenarios and strategies on how to realise them despite – and beyond – the present crisis situation.

People in power are not afraid of criticism; they live in a world of criticism from peers, the media and the citizens. What we can assume that they are afraid of is that there exist much better ideas and strategies than their own and that millions of people shall begin to do two things: 1) Ask themselves: Why did I not think of that? and 2) Decide to mobilise people for change with a positive vision based on the conviction that that is much healthier for me than becoming more and more frustrated by only criticising the present.

The idea that There Is No Alternative (TINA) – and therefore also only one narrative – is what politicians adore and cultivate on their way to authoritarianism. Democracy, in contrast, recognises that The Are Only Alternatives (TAOA) – and many possible narratives. TINA people see only the past and present. TAOA people see various possible and desirable futures.

That illustrates why research on peace and research on futures are so intimately connected—they are two sides of the same coin. Peace is about envisioning a future that is fundamentally different from the present, with its armament, militarism, warfare, social inequality, and far too much violence against other peoples, genders, cultures, and Mother Earth. Peace is about how we can realise (hidden) potentials that are now being violently abused by the dark forces of the present.

In other words, we are grappling with this issue: What kind of (academic) thinking promotes democracy, vibrant societal dialogues and strategies for constructive change – what serves to create “critical mass” for nonviolent revolutionary change for the betterment of humankind – and before it is too late? What can liberate our minds from the dystopian, repressive past and present and free our minds for the future?

This is probably where the traditionalist, positivist empirical science advocate would break in and say: No way! You cannot call it science if there is no empirical evidence – and you cannot produce empirical evidence about the future, because – simply put – it does not exist yet and cannot be measured by any method.

My answer is: “That’s outdated thinking by which you only focus on the past and the present, dear colleague! We cannot change the past. And we cannot change the present before we know where we want to go. So how do you see the possible futures?”

As social psychologist Kurt Lewin argued in 1943, “there is nothing as practical as a good theory.” Good theories – and theories are nothing but ordered clusters of hypotheses – about the future are extremely practical.

Science simply can not leave the question, “What to do?” to politicians, who tend to be neither practical nor theoretical but stuck in the short-term present. Instead, as part of the research process, we must produce ideas and strategies beyond the present—expand the time and space horizons—and change the empirical reality until it fits our values of what is desirable, given what our empirical work has yielded.

George Bernard Shaw: “I dream of things that never were, and ask why not?”

That may sound like turning science on its head. Most social scientists were told during their education that we must revise our theory and its hypotheses in the light of our results until our theory fits reality. That, however, can never lead to change, only to confirmation of what is – and what is wrong.

That is what in Galtung’s brilliantly simple model above is called “constructivism.” Neglecting that is to just hand over social science to be (mis)used by people in power and signal that they, better than people in the know, can create a better world. That sort of thinking may have had some – empirical – value and relevance decades ago when creative, visionary politicians indeed did exist, but today’s general Western leadership exhibits no such qualities. For many, it seems that even thinking four election years ahead is too challenging…

One critical aspect of the constructivist approach is that it changes the discourse. When we present criticism of what there is, we operate within the discourse of the present; we re-act to something we do not like – say over-armament or threats of war. Arguing against that will always take place within the paradigm and the discourse of those we criticise. It is a fundamentally defensive strategy.

If, instead, you argue, “Why do you not avoid war by taking the following constructive steps towards conflict-resolution?” – you set the agenda, shapes the discourse, and puts the advocate of the negative present—of the war—in a defensive mode.

Another critically important aspect of this constructivist approach is that it offers much more positive energy. It can operate on empathy and good will, keeping people hopeful. It also does not imply an attack on anyone.

People can work for something for as long as it may take, but human beings tend to give up if they only fight against somebody or something and do not “win” relatively quickly; that is when they say: This is impossible, I give up. Or they continue struggling but are increasingly driven by anger and even hatred.

This may be a classical psychological observation – but there is at least one basic philosophical addition I’d like to make: Remember, that until we have tried to create that better world, we do not know what is possible and what is not. That is why it is too easy for traditionalists to just kill good ideas with – Oh, isn’t that unrealistic? Are you not too idealist/romantic/naive…?

When those words are uttered, it’s quite likely that something exciting, new and perhaps even correct has been said or done.

The beauty of constructivism is that it invites intellectual and practical experimentation. It is no coincidence that Gandhi’s most well-known book is entitled, “My Experiments With Truth.”

In what follows below, I make a modest attempt at practising what has now been preached.

Democracy

Popularly speaking, democracy is often equated with “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” as famously articulated by US President Abraham Lincoln. He did not say democracy because that word does not exist in any US foundation document. Jack Matlock, the last US ambassador to the Soviet Union, argues that:

“The fact is, the United States is not a democracy. That word does not occur in any of our foundation documents. It is not in the Declaration of Independence, or in the Constitution, or in the pledge of allegiance (‘to the flag of the United States of America and the republic for which it stands,’) or in the oath of office every federal official takes.

The United States is a republic which at present is controlled by an oligarchy. It is also becoming more authoritarian. The separation of powers among the three branches of government, essential to avoid autocracy, is deeply eroded.”

So, the leader of the democratic, free Western world is not (even) a democracy. Despite that – probably surprising to a few – democracy is a core feature of Western society, normally understood as representative parliament – i.e. in free elections, citizens vote for people to represent their interests in a parliament consisting of parties of which some form the government and some the opposition.

It must be added that democracy requires a reasonable level of knowledge and information that is freely available. For instance, while India is often cited as the world’s biggest democracy, 26% of the population (287 million people) is still illiterate.

So the “world’s largest democracy” also has the world’s largest population who can’t read and write. In comparison, China’s illiterate citizens make up about 3% and that country is regularly called a dictatorship by the West.

Furthermore, in a society where the persons running for office are – or have to be – extremely wealthy to pay for their campaigns and where large corporations make multi-million dollar contributions to certain candidates (presumably not out of altruism), falls outside a reasonable definition of democracy – even though they may also not be dictatorships; there are many stations in-between the two.

Whatever merits democracy can be said to have, it is not that easy to distinguish between the democracy propaganda and true democracy. More about that below.

Are young people giving up parliamentary democracy?

When I was in my high school years – a few decades ago – and wanted to contribute to changing society for the better, the most natural – and finest – thing to do was to join a political party. Not so today. My students in peace studies around the world often ask me at the end of a course when it is time to say goodbye whether I can help them somehow in making their career. Their career dreams may be to work for the UN, for human rights and the environment, start their own NGO with a peace profile or set up their own consultancy firm for a better world.

Significantly, over all these years, only one student asked me what I thought about contributing to peace and development by becoming a politician.

As is well-known, people today engage in social issues mainly through civil society and the use of social media and protests as their primary tools. This is good from most perspectives and holds fascinating prospects for de facto global citizenship and action, but it also does something to the old type of representative democracy populated by parties as they still make up the system’s main decision-makers.

When we talk about global crises, people think much more of the environment, identity issues or warfare than of democracy being in crisis. I think Western democracy is in fundamental crisis for at least the following reasons.

The crisis of democracy – selected points

1. The state is being challenged from below and from above.

Democracy is tied to the state, to “my country” where I go and vote, and not to the world society. But the state is getting weaker due to pressures from both below and above. It’s often stated that global problems can only be solved by supra-national co-operation but those issues are discussed in various interest and regional associations and ad hoc forums. There exist no democratic decision-making mechanisms at the global level.

2. Society’s economic issues dominate

The primary cluster of issues discussed in democracies is the economy, and that threatens to reduce democracy to the politics of the wallet. The pervasive focus on the economy signifies a) that national democratic politics conducted in parliaments functions to try to mitigate the effects of the economic globalisation that is roaring ahead, and b) that most of society’s problems and challenges are managed through economic parameters, the market. Or, rather, the marketisation/commodification of virtually everything. One may question whether in Western (neo)liberal societies, the market is more of a decision-maker than democracy itself.

3. Materialism over life values

Parliamentary democracy’s obsession with – capitalist – economics makes it uninteresting or unviable for those who believe that democratic debate should also deal with values, ethics, and concepts such as justice and peace. Over the last 2-3 decades, democracies have phased out every quality of intellectualism and philosophy – even public discussions of visions of a better future society citizens may want to prioritise.

4. A time horizon far too short

The perspective of 4 years – from one election to the next – is, of course, hopelessly inadequate in a world that is haunted by complex problems, the solutions of which would require that we all operated with time horizons of, say, 10-25 years, or more. The visionary politician who has a long-term vision simply doesn’t fit and can hardly be found in today’s Western parliaments.

5. National parliaments less and less important

Less and less of what decides the future of our countries is decided by national parliaments. Instead, the real binding decisions that influence our lives and those of our children are taken by larger, more distant and elite-based structures such as Wall Street, NATO, the EU, the IMF, banks, stock market manipulations, etc. When they have made up their deals, national parliaments have to cope with how to adapt and adjust to the global framework conditions.

6. Global economy and military but only national democracy

The most globalising sectors of our societies are the corporate world (think, for instance, of the global economy/market, exchange rates, borrowing, trade, investments, finance, infrastructure, global sourcing, etc.) and the military (think of weapons production, weapons exports, bases, interventionism, war planning, doctrines, long-range-missiles, satellites, navigation systems, anti-submarine warfare, regional and global wars, and nuclear annihilation).

The elites in those two spheres of society think globally. They see the world as one system in which to operate. While the nation-state—their own country—may be important to them, it is not their primary, chosen perspective in time and space.

Therefore, democracy’s perhaps biggest problem is that we don’t even have the embryo of a global democracy that can match these two powerful actors.

7. Politicians must choose between getting elected and speaking the truth

Candidates in democratic election campaigns can’t be honest even if they want to. Any candidate has to promise “gold and green forests” about how much better we will live and consume in the future if only we vote for her or his party. Someone who hopes to make a political career can’t tell the voting citizenry that we must also take some painful steps and give up some activities to save the planet for future generations. Power is about promises – whether kept or not after election day – and there is, therefore, very little “gold” and “green forests” left.

To a dangerously large extent, democracy now rests on pulling the wool over the citizens’ eyes when it comes to the state of the world and what it would take to solve, deeply and broadly, say the environmental problems.

In addition, democracy is a very slow decision-making process in a world where complex solutions are urgently needed.

8. Politics becomes public relations which replaces knowledge

Politics is increasingly seen and practised as a game, pragmatic navigation, positioning, and horse trading. In general, reforms, laws and political standpoints are marketed and sold to the citizens as if they were commodities. For that, you need short, punchy soundbites, spin doctors and marketing campaigns, whereas traditional public dialogues and debates throughout society are too time-consuming and imply a meeting between elites and masses (and could lead to a change in what decision-makers have already decided over and above their citizens’ heads).

Media developments are resulting in shorter and shorter statements. Everything must be expressed within a maximum of, say, 30 seconds, and the concentration span is decreasing. Deliver the essence in 30 seconds, or we lose our viewers! In terms of public education and furthering democratic debates, it’s a vicious circle.

This leads to personal positioning rather than perspectives of substance. As a politician, you don’t have to know much about the complexities of, say, the Middle East or Ukraine; it has become more important to be able to take sides—good guys versus bad guys. Narratives, which are often incredibly simplistic, are frequently imported from a power centre abroad, such as Washington or Brussels.

So, instead of publicly educational dialogues (exploring issues) and debates (allowing various standpoints to meet and be backed up by arguments), citizens are fed the typical sports match-like televised confrontations: Our policies are better than yours!

And the one who is most eloquent, deceives more smartly or is nicely dressed “wins” the confidence and the votes.

Thanks to modern communication and media demands, the time available for knowledge-based political decision-making has been reduced enormously during the last 20-30 years. This impacts the quality of most decisions negatively.

And like all coins, this coin has a second side: Corporations and their brands increasingly mix and melt into politics. For instance, the Edelman Trust Barometer for 2024 states that

“With politics top of mind for consumers, they see brand actions through a political lens: nearly 8 in 10 consumers feel brands are doing things they consider political or politically motivated. But consumers do not want brands to shy away from politics. In fact, they expect brands to address key issues like climate change, fair pay, reskilling, public health, and diversity, seeing their action as pivotal to societal progress. And 71 per cent of global respondents say brands must take a stance on issues when under pressure, while only 12 per cent say that brands must avoid taking a position.”

https://www.edelman.com/trust/2024/trust-barometer/special-report-brand/brands-frontline-strengthening-trust-political-volatility

In recent times, we have seen how corporations express/brand themselves as anti-Russian and pro-Ukrainian – while they lie very low when it comes to positioning themselves vis-a-vis Israel’s genocide on Palestinians.

To summarise, while Western society’s political sphere becomes more commercial and market/marketing-oriented, the economic sphere—corporations and their brands—seems to become more political. These long-term trends may further undermine the ’classical’ theory and practice of democracy.

Closely related to these two sides of this coin – that cannot, however, have three sides – is that money influences and corrupts politics. In almost all constitutional democracies, citizens and corporations can donate money to election campaigns and political parties. The point hardly needs elaboration, also not right after the US elections in the autumn of 2024. And it is all stated succinctly in a book from 2002 – “The Best Democracy Money Can Buy” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Best_Democracy_Money_Can_Buy by Greg Palast https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greg_Palast

9. Politics as a calling versus a career path

Once, politics had a focus on aiming to promote a particular future development, and ideological differences between parties were visible. Today’s politics has become more of a profession, a career option; you take some years in politics and then go on to corporate business board rooms or whatever that may give you fame and funds.

People with a burning passion for some social issue choose not to become politicians but instead join NGOs, blog, do social media or become entrepreneurs. As my students mentioned above have taught me. Politics, rather, attracts people without such passion – except perhaps for personal privileges, limousines, and frequent 1st class travels paid by taxpayers. And, not to forget, for the attraction to power.

This means that politics no longer attracts the visionary leader, the charismatic personality type who can inspire the young, those for whom politics should be made.

With the standard exception stated – and there are individual exceptions to the above – most politicians lack humour (at least on-stage), charisma, enthusiasm, personality and vision – combining to make democratic activities and debates utterly boring most of the time.

10. Democracy is about voting but not about selecting

Most people rightly believe that democracy is distinguished by the citizens voting for some person or party and laws or voting yes or no to some alternatives set up by the political elites (also called referendum).

But democracy’s fundamental idea is not to vote on an issue set up in advance by people we do not know. Democracy is – should be – to contribute to establishing the agenda in the first place.

Democracy is also not to decide between only two alternatives, like: Shall Switzerland remain a neutral country in the future? Yes or No! Ideally, it would be to develop a broader spectrum (moulded and changed by public education and debate) of which, say, neutrality is only one option/alternative among several.

Genuine democracy is about setting agendas. It’s not about voting yes or no to somebody’s pre-determined and more or less cunning agenda and candidates.

You could, perhaps, summarise it all by saying that democracy is no longer lived, it is being performed. It’s become a ritual without much ethos.

11. Citizens’ sense of not getting through to decision-makers

The sentiments expressed by an increasing proportion of citizens in the Western world is that it is extremely difficult to “get through” to the people who make decisions on the top. That is, frankly, my own experience over the decades, too.

Compared with a few decades ago, these top decision-makers also seem to feel it less important to be in direct dialogue with their constituencies. While before, it was a duty to send answers back to a citizen in an envelope, they no longer receive even an email or other response when writing to their representatives or ministers. The political system has its gatekeepers, and even if you send constructive proposals or research reports to politicians, it is naive to expect a reply, acknowledgement of receipt or a word of thank you. The same, by the way, applies to attempts at communicating with the media world.

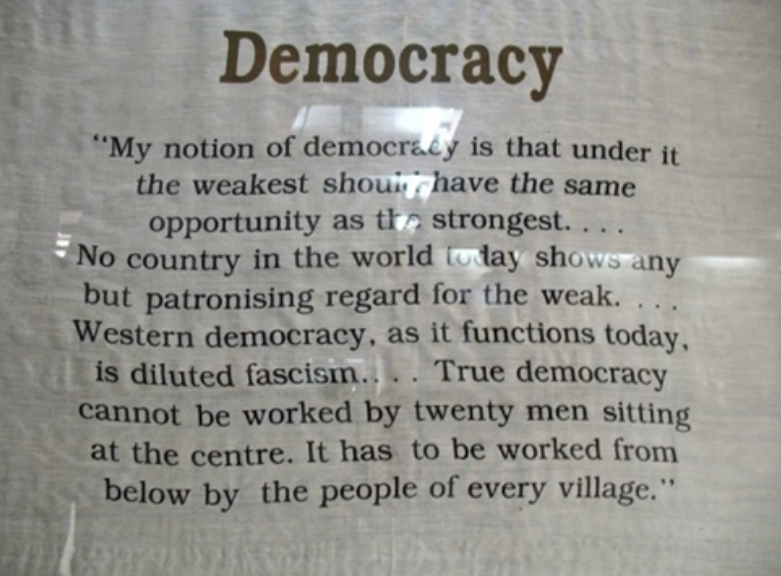

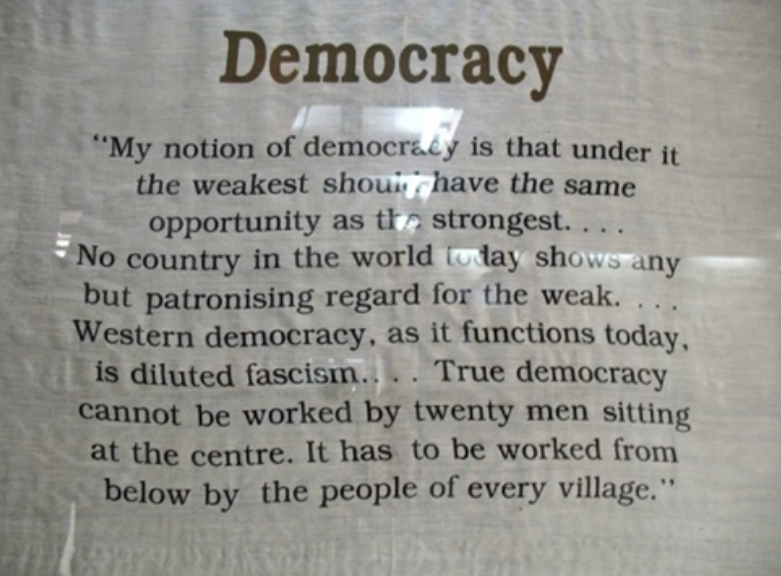

In summary, I find it difficult to disagree with Gandhi’s radical criticism almost a hundred years ago:

Mohandas K. Gandhi’s famous statement

In one of his last interviews, French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905~1980) said that every time a citizen votes, s/he gives away power. That statement points to the essential, classical distinction between representative democracy and direct democracy. In the first, the voter delegates to someone else who has convinced/seduced her or him to take care of citizens’ interests.

We know this generally leads to false promises and considerable disappointment with politics. In the second, citizens take issues into their own hands—which, of course, has disadvantages and encompasses a whole series of other problems, not the least of which is how to organise it. That said, without a vibrant, active, and educated citizenship, genuine democracy becomes impossible.

Least bad but far from good enough

In summary, while democracy perhaps still remains the least bad system, we should take care not to equate that statement with democracy being good enough.

Comparing Western democracy with authoritarian regimes over time does not prove its quality or perfection. Every good system can and should be improved—i.e., we need to democratise democracy to simplify it a bit. At least some elements of it ought to be taken to higher levels—globalising democracy to democratise the globe and its outdated Westphalian-national(ist) decision-making procedures.

Secondly, Western democracies will have to accept and respect that there can be non-Western models of democracy and that these are not necessarily un- or anti-democratic and should not necessarily be fought. No system should become universal. We are all better off with unity in diversity, also when it comes to democratic governance.

Complacency in this matter could easily and rapidly lead the West towards the authoritarianism that it maintains that it is the antidote to. Such indicators are already flourishing…

UN reform and global governance

The United Nations, the world’s single most important peace-visionary organisation, turns 80 on October 24, 2025. Since its establishment in 1986, TFF has been focused on promoting Article 1 of the UN Charter, which states that peace shall be brought about by peaceful means.

That is a Gandhian inspiration. As he said “the means are the goals in the making.” You can not use destructive means to achieve constructive goals.

Regrettably, people often accuse the UN of being too expensive, too bureaucratic, too ineffective, too corrupt, or too this and that.

Here is why this author considers such statements intellectually poor – and dangerous too:

First, as Norwegian Trygve Lie, the UN’s first Secretary-General, stated, the UN will never become stronger or better than its member states want it to be. Sadly, they are still far more nationalist than globalist.

Lie’s words are still spot-on correct. They simply mean that it is the member states (some more than others) that behave internationally and in their UN policies in ways that weaken the world organisation and its norms, undermine its power and role, and marginalise its operations.

Secondly, those who say that the world could just as well close down the “outdated” UN just don’t consider how small its budget is and how impossible it would be to make the world a better place with so few funds, given the destructive forces that are pitted against the UN and its norms by the world’s MIMACs – Military-Industrial-Media-Academic Complexes.

The UN regular budget for 2024 is USD 3.59 billion, nearly USD 300 million more than the previous year’s budget. This budget supports the core functions of the UN Secretariat and includes funding for various operations, including peacebuilding efforts. The total annual expenditures of all its member agencies (such as WHO, UNICEF, etc.) are US$50-60 billion.

Now, compare that with the costs of global militarism: Today, the UN members spend the highest-ever total global sum on military expenditures, US$2400 billion.

This means that world military expenditures are 666 times larger than the UN’s regular basic budget, including peacekeeping and about 40 times larger than the sum of all the – good – things the UN and its family organisations do.

What fires can you prevent or extinguish if militarist pyromaniacs have 40 times more resources at their disposal to start new fires? Admittedly, this is a rhetorical question, but it makes an existentially important point: The world’s priorities are absurd, if not perverse, and there are still virtually no discussions of these priorities.

Most people seem to accept that this unimaginable waste of humanity’s resources is the price to pay for what is euphemistically called ’security’. However, as of writing this at the end of 2024, warfare is looming large, at least in Europe, and virtually all countries worldwide plan to increase their military expenditures.

Thirdly, whether intended or not, these critics implicitly say: We’d rather have a world run by the US Empire (and a few others) than by the UN. This is a dangerous way of thinking that totally undermines international law and the extremely important UN Charter – the most Gandhian document the world’s governments have ever signed.

It deserves to be pointed out that at this particular moment of global and UN history, there are reasons to be extremely concerned about the very future of the United Nations in the light of US President Donald Trump’s attitude to the UN and the people he has appointed to manage the UN policy of the US. See Thalif Deen’s “US Envoy-in-Waiting Blasts UN as Corrupt – & Threatens Funding Cut” at the Inter Press Sevice of November 29, 2024.

This is definitely not the time to criticise “the UN” as such, at least not without also presenting visionary reform proposals and proposals for global governance.

There is no doubt that saving humankind and our common global future goes through the United Nations and its Charter norms – not as the only change-maker but as the most central.

It is certainly true that the UN must be reformed. But as we show below, governments and people, including the media and politicians, need to reform their attitudes and policies regarding the UN much more.

When we give it a more profound thought, this issue is part of a much larger process of democratising decision-making beyond the national and regional level and begin to think of global governance in completely new, future-adapted ways.

If and when humankind develops something far better than the UN, we may switch to that and close down the UN as we know it today. But not a second before that has happened.

And that new institution shall not be located in the member state that has harmed the UN the most. But until that moment, let’s make the present UN stronger so it can eventually do what it was intended to: Serve the common good and abolish war – and make peace by peaceful – civilised – means, thus making the use of collective violence the absolutely last resort.

“We, the people” must work on that from below since “They, the governments” have consistently violated that tremendously important Article 1 and the entire normative framework embedded in the UN Charter. And continues to do so!

Below, please find a series of proposals for global democracy and a strong UN. Some will surely find proposals such as these “unrealistic” or “romantic.” That’s what many also thought and said when it was suggested that slavery should be abolished, when Europeans protested the deployment of nuclear intermediate-range missiles in the 1980s and did get rid of them, when it was predicted that the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact would soon dissolve and the Berlin Wall come down…or when people started campaigning to reduce smoking tobacco…

Let us first focus on democracy in relation to the United Nations. It deserves emphasis that there are many problems pertaining to democracy and the global system (we avoid calling it ’the international community’ since inter-national is an outdated term, the US has misused it for the Western world only, and ’community’ de facto doesn’t exist in these times where the West is self-isolating through rampant militarism and confrontational policies).

First, democracy itself is a complicated term and what philosophers call an essentially contested concept. But this is not the place to write a treatise on what democracy is philosophically.

Second, what to do with the fact that democracy, although perhaps being the least bad theory so far, is considered “pseudo” and ineffective and is systematically circumvented by a number of power elites in the Western world (and Japan)?

Third, it is a Western-biased concept that is most often taken to imply only elements such as a multi-party system, equality before the law, free speech, free elections and a set of social institutions such as parliaments and the free press. Thus, many considered the Soviet Union a dictatorship because it has one party and the United States a democracy because it has two parties. However, true democracy is also about a special political culture that naturally seeks to incorporate non-majorities.

Fourth, while democratisation is desirable, how do we avoid, on the one hand, the politico-cultural imperialism of universalising a deeply Western definition and concept/theory and, on the other, the cultural particularism in which any system or dictator is permitted to call a society democratic with reference to local values and interpretations?

Fifth, there is no democracy at the international level, no institutions that resemble those of the nation-states; therefore, we will have to build on the only globally-oriented institution that can be reformed in the direction of a multi-cultural democratic institution at the supranational level: the U.N.

But the UN itself must be democratised, and it must come to embody, sooner rather than later, a democratised world order. It is time to take “we, the peoples” seriously and look into which peoples should be given a say in world – and UN – affairs. The catchword here, of course, is popular sovereignty, i.e., a systematic acknowledgement of the principle that sovereignty resides with the world’s peoples, with global citizenry.

Sixth, as pointed out by Gandhi, democracies are based on regress to violence (armies, state repression, prisons, courts, capital punishment, etc.) to uphold their order. And all democracies, with exceptions such as Costa Rica, Iceland and perhaps a few more, profit/benefit from arms exports and they support, more often than not, political interventionism and nuclearism. In other words, Western democracy and Western militarism are deeply intertwined – although it is still empirically true that democracies usually don’t go to (military) war with other countries they consider democratic – which does not exclude that economic warfare can be pursued.

Seventh, the same could be said about the attitudes in most democracies about the relationship between society and Nature. Modern democracies’ complete, general entanglement in capitalism entails environmental destruction. The democratic world, not communism or dictatorships, chops down rain forests and kills species, languages, and “primitive” cultures, and it has done so for centuries.

Fortunately, the environment and socio-economic (mal)development serve more convincingly than any other problem as arguments for restructuring existing international organisations, creating new ones, and changing the meaning of government politics to encompass the regional and global levels.

This is what eco-politics is about.

Today, the United Nations is totally unable to deal effectively with this civilisational challenge. The fact that sustainable development is a concept that has come to stay points to the necessity of establishing an entirely new organisation within the United Nations. Additionally, the environmental agenda is the one that, more than others, seem to reflect the common interest of all humankind.

In 1991, the Board of the Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research, TFF, in Sweden published TFF Statement # V entitled A United Nations of the Future. What ‘We, the Peoples’ and Governments Can Do to Help the U.N. Help Ourselves.

In it, we suggested radical reforms in peacekeeping, development and environment and democratisation of the U.N. itself and of the world community.

Here follow some of the proposals – revised, re-phrased and updated where necessary:

• The UN Security Council must be reformed and the veto power be restricted.

The exceptionally strong influence of the five permanent Security Council members is incompatible with any conceptualisation of global democracy. Likewise, its composition does not reflect the global society and its dynamic changes.

Perhaps there should be no permanent Security Council members – and certainly not those that are the most highly armed, war-fighting and nuclear states? Perhaps there ought to be a Security Council with no permanent members but a Council where membership changes at intervals so that, over time, all member states have taken their turn at the Security Council?

The veto power of the permanent members of the Security Council (SC) ought to disappear or its use restricted to certain areas and situations. Instead of the veto power, the SC could work with a double majority among the permanent members and among the elected members. Whatever we prefer, we can no longer ignore the need for a comprehensive reform of the Security Council, its membership criteria, and modes of operation.

We believe that a gradual fading away of the veto power is not only desirable but also possible. Furthermore, it is important to strengthen the remunerative, peaceful and democratic powers of the Secretary-General and a new leadership structure as well as the General Assembly in the future rather than relying on the negative power of the veto. Hence:

• The UN needs a stronger Secretary-General and a new leadership organisation.

The provisions for the functions of the Secretary-General (particularly Articles 99 and 100) are, in fact, the only concession made in the Charter to supranationality. However, to fulfil all the requirements of a Secretary-General laid down in the Charter and practices developed since then, not to mention the personal qualities demanded, a superhuman personality is required.

Collective leadership in the top echelon is now a necessity. It could consist of five: the Secretary-General him- or herself, the three deputies – for peace and security, economic, environmental and social matters and for administration and management. The fifth would be a new deputy in charge of relations with the public, the non-governmental and the private sector.

• The General Assembly should be invigorated.

The General Assembly (GA) may have the most important role in the future in raising political awareness on global issues. It could sponsor Special Sessions to communicate the facts, evaluations, and urgency to a broader audience.

The GA’s legislative authority needs to be binding and linked to actions decided upon simultaneously (as well as their financing). It has to be a consensus decision, and there need to be legally binding conventions. The November 1950 “United Action for Peace” Resolution provided that the General Assembly would meet to recommend collective measures in situations when the Security Council was unable to address a breach of peace or an act of aggression.

• The UN needs new constituencies.

The United Nations is, in fact, the United Governments. It is beyond doubt true that a number of governments are de facto “non-people organisations” (NPOs), whereas many civil society organisations, or so-called NGOs, are genuine People’s Organisations (PO) but have no access to the “We, the People” UN and its various forums. (Regrettably, there is also an increasing percentage of NGOs that, due to financing and leadership, could more precisely be referred to as Near-Governmental Organisations).

So, new actors should be brought into the picture in various ways and with guarantees that they are truly independent of states and governments. We suggest the following categories: a) international organisations, b) transnational organisations, in which people represent causes or worldwide issues but not parties or countries, such as various movements and initiatives, c) minorities and indigenous peoples, d) refugees and displaced persons, e) children and youth under 18 years of age and f) transnational corporations.

• Establish links and consultative processes between all these NGOs and all UN bodies – and using hearings.

Consultative status, direct participation in commissions and agencies, an elaborate system of hearings throughout the UN system, sounding of analyses and proposals and inviting statements, commissioning fact-finding, research, etc., with these organisations – are all measures that exemplify how much-needed democratisation combined with the collection of knowledge and innovative perspectives – can be implemented even if step-by-step.

Effectively tapping non-governmental resources would enrich the UN tremendously and transform it into a much more dynamic body perceived by citizens worldwide as relevant to them.

• A Citizens Chamber or Second Assembly must be developed.

One can only sympathise with the often proposed Second Chamber or “parallel structure.” It would probably be wise to introduce it gradually and to establish first which constituencies it should have (see above) and how to elect them.

• Direct election of UN representatives.

Today, Ministries of Foreign Affairs appoint their country’s UN Ambassador and staff. Citizens have no chance to influence who will represent them—“We, the peoples.”

This creates a sense of distance. However, nothing in the statutes of the United Nations forbids any member from appointing their representatives by direct election, but obliging them to do so would hardly be possible today.

For other bodies than the General Assembly such as for agencies and the proposed Second Chamber of non-governmental actors, citizens should be given the opportunity to vote for candidates.

• The United Nations must be “sold” efficiently as a global media.

More or less important news – combined with sport, entertainment, debates, etc – reaches the world 24/7, either in the traditional ways or through social media. But the United Nations has no similar structure with commercials, educational programs, debates, entertainment, no campaigns, no reports and no debates and analyses that reach us daily.

The UN is much too much at the mercy of the Western mainstream press.

Most UN documents and even public information materials appear anything but stimulating to ordinary citizens. We live in the age of global, digital, multi-channelled communication, and the UN must develop a creative media competence and worldwide daily presence as well as find sufficient funds to reach into our living rooms – at least to the same degree public service broadcasters, CNN, BBC or CGTN do. The UN Department of Global Communications does a lot of good things, but it will need resources to reach the level of the mentioned media, to distinguish itself in the future as the go-to source for world news, events, trends and discussion of them.

https://www.un.org/en/department-global-communications/news-media

And, now, what can the member governments do?

• Members must integrate UN norms and long-term goals into their national decision-making and give up some of their sovereignty

Obviously, the nation-state is losing influence over transnational actors and the environment. Governments should acknowledge that while they give up some sovereignty now, they will later reap the benefits of cooperation, early solutions to problems, and order instead of chaos. Taking others into account, thinking globally and cooperating in new ways is the sine qua non of survival for all.

The commitment of member governments can be seen from two angles: They can be encouraged to improve their policies and ensure that they align with decisions they have supported in New York. A more stern mechanism may also exist, namely, suspending members who repeatedly violate UN Charter norms, resolutions, and other decisions. The length of the suspension period should depend on the seriousness of their violations. That said, it may not be wise to permanently exclude any member.

• Members should develop true self-defence and new security policies.

Any national moves towards purely defensive military and/or civilian postures and doctrines would solve – automatically – a number of serious problems that would otherwise be dumped on the Secretary-General or settled through naked force in the battlefield.

The author has outlined such a possible system in a longer, detailed analysis published in 2023 by China Investment, entitled “Towards a new peace and security thinking for the multi-polar, cooperative and peaceful world.”

https://transnational.live/2023/07/23/towards-a-new-peace-and-security-thinking-for-the-multi-polar-cooperative-and-peaceful-world/

It argues for putting peace first and then securing it through defensive military and/or civilian defence measures that do not lead to arms races and threat perceptions and build on concepts such as human security from the local to the global, common security, prioritising civilian early conflict warning and mediation as well as conflict-resolution and a series of other constructive ideas. The fundamental idea of human civilian rather than national military security was developed by Johan Galtung and the author back in“The New Military Order – The Real Threat to Human Security. An Essay on Global Armament, Structural Militarism and Alternative Security,” Lund University Peace Research Department and the Chair of Conflict and Peace Studies, Oslo University, 1978.

• Members should allow for direct UN service.

Each member, through national law-making, ought to make it possible for any citizen otherwise eligible for military service to seek recruitment with the United Nations for military and civilian peacekeeping on an equal basis with national conscription.

• Members should refer more conflicts to the United Nations.

Past analyses showed that only around 32% of all disputes involving military operations and fighting were referred to the UN during the 1980s, the lowest share since 1945. Although data for today are difficult to come by, one must doubt that the level is higher today.

Right now the truth is that never before have there been so many armed conflicts across the globe.

https://www.uu.se/en/news/2024/2024-06-03-ucdp-record-number-of-armed-conflicts-in-the-world

Imagine that the whole range of ecological conflicts developing these years would also be referred to the UN.

Or imagine that the war in Ukraine and the underlying NATO-Russia conflict had been referred to the UN already in 2014, and UN peacekeepers had been deployed to southeastern Ukraine years before the Russian invasion commenced.

At the same time, a recent 2024 study by the Carnegie Endowment for Peace summarises:

“The quantitative data show that UN peacekeeping “has a large, positive and statistically significant effect on reducing violence of all sorts.” The findings are so strong that there is no question that peacekeeping reduces deaths, sexual violence, refugee flows, and the likelihood of the recurrence of conflict. Where there are peacekeeping missions, lasting peace agreements are more likely. In short, UN peacekeeping is extremely effective at bringing peace. Moreover, interstate wars have declined overall since World War II, in part because states have often chosen to work through the Security Council to resolve interstate conflict.”

See “Can the UN Security Council Still Help Keep the Peace? Reassessing Its Role, Relevance, and Potential for Reform” at

https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2024/07/can-un-security-council-still-help-keep-the-peace?lang=en

Therefore, there is all the more reason to argue for the world to use the UN more —the organisation with the longest accumulated experience in peacekeeping and peacebuilding. NATO shows no such results.

• Members should re-affirm their Charter obligations and develop common-sense coalitions.

This applies particularly to those relating to the non-use of force and the peaceful settlement of disputes, respect for the spirit and letter of the Charter combined with a firm commitment to make available all kinds of civilian and military peacekeeping forces as well as all expertise relating to non-violent, peaceful conflict resolution.

There is a need for a “new, common-sense coalition” consisting mainly of middle-size and non-aligned countries determined to use the UN machinery effectively. Common sense coalitions will be needed not only in the field of peacemaking but also in creating genuine, globally sustainable development and ecological security. The UN is no substitute for governmental action.

It is noteworthy that China is the only one among the UN heavyweight members which often and consistently emphasises the important role of the UN.

• Increase the UN budget substantially and share the burden of the future UN budget more equally.

No member should be allowed to exert political pressure within the organisation because of the size of its financial contribution. No member should contribute more than, say, 10% of its budget. Sharing in relation to the size of the population and/or GNP may be the easiest, with compensation for the poorest, i.e., resembling some kind of progressive taxation or tiered membership fees.

There is no doubt that, unfortunately, the UN is a heavy bureaucracy that needs to be streamlined and operate more efficiently. But there is also no doubt it is pitifully under-financed (as we have pointed out above). The entire staff of about 50,000 is equivalent to 1/8 of the world’s military researchers and engineers or half of the people employed in the British rail sector.

We doubt the bureaucratic problem within the UN is that much worse than in most other large organisations, say, NATO, the EU or the Pentagon. Evidently, it should be rationalised and better coordinated, and deep cuts should be made in extravagant salaries, per diem, and travel costs.

Having said that, the UN will need resources many times what it receives today to be an effective actor in the future world community. It is a shame for the world’s governments that the UN is constantly forced to live close to bankruptcy and that leading members ignore honouring the deadline for payments.

There are at least two ways in which the United Nations could supplement its budget: One, members could earmark a certain minimum percentage of personal income and consumption taxes or GDP. It would make much more sense than the idea to set off 2-3% of GDP for the military, irrespective of any threat assessment.

Two, the United Nations and its organisations could raise funds from not-for-profit foundations, small and big private donors worldwide. Undoubtedly, many citizens would be more happy to see their tax money end up at the UN than as contributions to their government’s militarism and warfare. The criteria must, of course, be that no formal or informal strings be attached.

• Member parliaments should establish multidisciplinary monetary UN committees.

They should be staffed with experts, politicians, public servants, and representatives of movements, minorities, refugees, children, and youth. They should be charged with raising issues, presenting proposals, holding hearings, etc.

Each such national committee would monitor their nation’s policies and programs for the UN and its agencies and help create a much wider public consciousness on world affairs. It should carry out “global impact assessments” of national decision-making, preferably in cooperation with UN agencies and regional bodies.

It could also facilitate better national and regional coordination of UN activities. While governments often demand “improved coordination” of the UN, they themselves have created a loose system and often fail to coordinate their own policies in different forums within the UN system.

• Set up UN “embassies” in member states with transnationally recruited teams.

They could operate together with the United Nations associations and monitor security, development and environmental policies and actions and report back to regional organisations,

UN agencies and central UN bodies on these matters. Naturally, they should place their advice and analyses at the disposal of governmental and non-governmental groups and associations, as well as explain UN affairs to the media.

In other words, they would serve as “go-betweens” in each country, with consultative and observer status and no more. They would make the presence of the UN and its norm system felt locally and balance the governments’ representatives to the UN. This is an obvious solution to the problem of the very low worldwide profile of the UN.

It is essential that these bodies monitor the degree to which national decision-making is aligned with decisions the countries have endorsed at various UN bodies. While they may not be able to prevent a country from going to war and violating a series of Charter provisions and resolutions, they would still make a point and contribute to other bodies whose role is to hold decision-makers accountable according to international law.

• We should revise the UN Charter so it gives appropriate attention to environmental issues.

The Charter does not mention environmental problems or ecological balance at all. Peace is understood as non-war between governments and not as harmony between Nature and human beings.

Few would dispute today that the two are intimately linked and that peace with Nature is existentially important.

• An Environmental Security Council (ESC) must be set up and given very comprehensive authority and peaceful enforcement capacity.

It will have to have very extensive non-violent powers but operate in a manner totally different from the present Security Council. It should deal with all matters related to issues such as global warming, ozone layer depletion, pollution, waste, ecological assessment (also of consumerism in rich countries), clean water and air, urbanisation, transport systems and infrastructure. Further it should decide global environmental standards and depletion quotas of threatened resources and energy sources.

• A Declaration of Human and Governmental Duties and Obligations.

The United Nations, its Charter, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are “anthropocentric,” placing the individual at the centre of all concerns. The UN should strive to establish a normative framework that integrates humankind and Nature.

Even if we cherish and care for Nature and its bio-diversity in consideration for human beings or believe that Nature has rights and values in and of itself, we shall not be able to solve the environmental problems – climate change – and learn to live in sustainable ways without a concept of human duties and obligations vis-a-vis Nature.

Gandhi’s succinct argument that there can be no rights without duties is as simple as profound. It is time that the United Nations, in cooperation with all relevant constituencies, begin the work of drafting a “Universal Declaration of Human and Governmental Duties and Obligations”. The Earth Charter can deliver some of the inspiration for such an endeavour.

More about this dimension here – and see Note 1.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ujIQBB9aarU&list=PLYF0JPfanRdzMRORJokjTmzZWXIP9juG0&index=96

and here in an earlier article kindly published by China Investment:

https://transnational.live/2023/07/23/towards-a-new-peace-and-security-thinking-for-the-multi-polar-cooperative-and-peaceful-world/

• Demilitarization of the common heritage and protection of parts of the earth.

The Environmental Security Council (ESC) should cooperate with the existing Security Council about demilitarising humanity’s common heritage and developing a global governance over the parts of the earth not now under national sovereign control: outer space, Antarctica and the high seas. Closely related to that is the implementation of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, or the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty, of January 2021. Nuclear weapons are based on the philosophy of terrorism and are part of the ’balance of terror.’ Were they ever used, the consequences for humans and for the environment/Nature could amount to omnicide and ecocide.

• The Trusteeship Council could be revitalised.

Today it is virtually without tasks and could be given authority over the common heritage areas, resources and culture. The modalities for such a new, much larger role for the Trusteeship Council should be investigated and proposals made.

If territories, resources and various objects could, either permanently or for limited periods of time, be entrusted to the United Nations, it would solve many problems and reduce environmental damage.

• UN protection and management of humankind’s most important resources and species.

We think here of resources such as oil, rain forests and resources threatened by depletion that could be protected and managed by the Trusteeship Council. Depending on the circumstances, the Council would cooperate with the ESC and perhaps the SC. Setting depletion quotas for resources and reduction standards for threatened species should become the prerogative of this part of the UN system.

• A UN ecological security monitoring agency and regional eco-security commissions are needed.

The first step would be to coordinate existing institutions worldwide. For the first time, the word “regional” would not mean political or geographical but biological or ecological regions. Governments and many other actors would cooperate in new bio- or eco-regional patterns, often crisscrossing other types of boundaries. The commissions would report directly to the Secretary-General.

In lieu of a conclusion

Global democracy is much broader than what pertains to national democracies and the globalisation of democracy discussed above. The UN that we have focused on is not the only, albeit the most important, supra-national organisation; let us think also of all the rising regional organisations and various types of governmental groups such as NATO, ASEAN, SCO and BRICS+ where ministers or heads of state meet, discuss and issue a resolution most often without the slightest anchoring among the people they purport to represent and often with Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) petitioning indoors or demonstrating outdoors.

There is a very long way to go.

It’s fairly easy to continue proposing reforms and putting them up for reflection and global dialogue. If multi-national and multi-cultural future workshops—a method for generating constructive ideas and visions of the possible futures associated with Austrian future researcher Robert Jungk—were to become frequent events worldwide, only humanity’s collective imagination would set the limits.

Outside the elite circles that mastermind the present trends, which point toward a partial or complete global breakdown, there is boundless creativity under the sky.

The world will be looking intensely for good ideas about global governance and peace – after nationalism, militarism, racism and imperialism, as well as other constructs of lesser minds have declined too.

Why not let thousands of flowers bloom for humanity’s better future already so we can rationally prepare for a future that is still eminently possible and can be developed only through global democratic dialogue?

Note:

1. What follows from that point in the article was written in 1991 when I served as a visiting professor at the International Christian University, ICU, in Tokyo. It was published in “Alternatives To World Disorder In The 1990s” – Educational Series Nr 25, Institute of Asian Cultural Studies. Parts of it can be read online here:

https://transnational.live/2018/12/10/at-70-a-few-problems-with-the-human-rights-concept/.

“一般人看到已经发生的事情而说为什么如此呢?我却梦想从未有过的事物,并问为什么不能呢?”

——乔治·萧伯纳(1856~1950年)

爱尔兰剧作家、评论家、辩论家和政治活动家、1925年诺贝尔文学奖获得者

导言——为什么科学必须关注可能的和更美好的未来

本文写于瑞典,在欧洲,战争的风险——很可能是北约与俄罗斯之间的常规战争——明显增加。我们所处的时代特征是,人类最紧迫的生存问题未能得到解决,如减少贫困和军国主义,以及阻止被委婉地称呼的气候变化,即全球环境变暖和对环境的严重破坏。

因此,可以说,按照基本标准来衡量,全球系统正在接近极限,超越极限后一切将难以复返。在极端情况下,使用核武器将意味着(人类的)大屠杀和(自然的)生态灭绝。

因此,难怪许多人对现实视而不见,沉迷于娱乐,关注自己的身份和外表,并在“近乎”日常的活动中对新闻中的内容感到无助或沮丧(如果他们还没有完全放弃新闻的话)。

虽然从心理上讲这是可以理解的,但这对每一种民主制度和拯救世界或至少在某种程度上改变世界的前景来说都是毁灭性的。

然而,这种无望和逆来顺受的反应——从人类更广阔的层面上逃离,进入“我”的文化、游戏世界、愉悦的逃避活动等——恰恰是社会当权者的目的所在。这正是社会权力人物所希望他们的公民做出的反应。如果他们的公民已经放弃参与社会和更广阔的世界,那么精英们就可以更容易地做出对自己有利的决定。

我不想说得过于道德化,但在我看来,这不是知识分子或真正致力于变革者的选择。我认为,发挥想象力,勾勒出具有建设性的“未来”和实现这些“未来”的战略,并将其公之于众,避免唯我独尊和失败主义,是一种职业责任。

这一观点背后有各种原因。

和平研究者必须从甘地的“建设性纲领”和马丁·路德·金的“亲爱的社区”中得到启发——即必须进行建设性思考——或者,正如人们常说的:即使明天世界可能毁灭,也要种一棵树——或者,点燃一支蜡烛,而不是诅咒黑暗。

改变世界,无论大小,都不能只靠经验性地了解什么是错的,或批评什么是做得不对的。

它只能是建设性思维与愿景的结果——是我们为之奋斗的东西,而不仅仅是通过反对某些东西来实现的。

和平与未来研究的先驱约翰·加尔通(Johan Galtung,1930~2024 年,我的导师之一)认为这是科学调查不可分割的一部分。因此,我们在社会科学领域所做的工作,特别是和平与未来研究,是数据、理论和价值这三者之间的相互作用:

经典但有限的科学过程包括提出关于世界如何运作的假设,使用一致的方法对其进行测试,并得出有关世界的可靠和有效的结论。这是自然科学的主要范式,但对于社会科学来说,却远远不够。

萧伯纳说:“一般人看到已经发生的事情而说为什么如此呢?”

在社会科学中,我们必须承认,我们正在研究的东西,从根本上说,是我们自己的一部分。这意味着我们要非常清楚自己的价值观,以及它们如何影响我们的解释。

不可能有完全客观的真理——客观性不过是主体间或者多主体性:一些科学家对世界的运行方式得出了相同的结论,他们可以用相同质量的方法来证实某件事情。哪怕只有一个人用同样的方法得出了另一个结果,那么这个理论就不能被证实。但它仍然可以被讨论,并引发新的、不断完善的研究。

这就是和平研究与另一门以目标为导向的科学——医学——的相似之处。

好医生会根据知识和经验做出诊断,但不会给病人留下“病人很快就会死去”的预言。医学的一个绝对基本要素是回答基本问题: 根据我们已知的知识,如何才能创造健康并防止疾病复发?这就是针对个人的治疗或疗法,同样,和平与未来研究产生的正是这种类型的未来思维、愿景——简单地说就是新概念和好主意——在更高的层次上:如何创造一个更美好的世界,以及如何在当前的危机情况下——甚至超越当前的危机情况——制定实现这些目标的方案和战略。

当权者并不惧怕批评;他们生活在同行、媒体和公民批评的世界里。我们可以假设,他们害怕的是存在比他们更好的想法和策略,害怕千百万人开始做两件事:(1) 问自己:为什么我没有想到这一点?(2)决定动员人们以积极的愿景进行变革,因为他们坚信,这对我来说要比只批评现状而变得越来越沮丧,要健康得多。

没有其他选择(TINA)——因此也只有一种说法——是政客们在走向专制的道路上所推崇和培养的理念。与此相反,民主承认“只有选择”(TAOA)——以及许多可能的叙事。TINA的人只看到过去和现在。TAOA的人看到的是各种可能和理想的未来。

这说明了为什么和平研究与未来研究如此密切相关——它们是一枚硬币的两面。和平是对未来的憧憬,它从根本上不同于当前的军备、军国主义、战争、社会不平等以及对其他民族、性别、文化和地球母亲的过多暴力。和平是关于我们如何实现(隐藏的)潜能,而这些潜能现在正被当前的黑暗势力粗暴地滥用。

换句话说,我们正在努力解决这个问题: 什么样的(学术)思想能够促进民主、充满活力的社会对话和建设性变革的战略——什么样的思想能够为非暴力的革命性变革创造“临界质量”,以改善人类——而且是在为时已晚之前?怎样才能把我们的思想从过去和现在的去乌托邦式压抑中解放出来,让我们的思想面向未来?

传统的实证主义经验科学倡导者可能会在这个时候插嘴说:“不可能!”:如果没有经验证据,你就不能称之为科学——你也无法拿出关于未来的经验证据,因为——简单地说——它还不存在,也无法用任何方法来测量。

我的回答是:”亲爱的同事,你这种只关注过去和现在的想法已经过时了!我们无法改变过去。在我们知道要去哪里之前,我们也无法改变现在。那么,你如何看待可能的未来呢?

正如社会心理学家库尔特·卢因在1943年所言,“没有什么比一个好的理论更实用了”。关于未来的好理论——理论不过是有序的假设群——极其实用。

科学不能把“怎么办?”这个问题留给政治家,因为他们往往既不务实也无理论,而是停留在短期的当下。相反,作为研究过程的一部分,我们必须提出超越现在的想法和战略——扩展时间和空间视野——改变经验现实,直到它符合我们的价值观,即根据我们的经验工作所得出的结果,什么是理想的。

萧伯纳:“我梦见从未有过的事物,并问为什么没有呢?”

这听起来像是在颠覆科学。大多数社会科学家在接受教育时都被告知,我们必须根据研究结果修正我们的理论及其假设,直到我们的理论符合现实。然而,这样做永远不会带来改变,只会证实什么是对的,什么是错的。

这就是加尔通在上述简洁明了的模型中所说的“建构主义”。忽视这一点,就等于把社会科学拱手让给掌权者(错误地)使用,并暗示他们比知情者更能创造一个更美好的世界。几十年前,当富有创造力和远见卓识的政治家确实存在的时候,这种思维或许还有一些——经验上的——价值和意义,但今天的西方领导层普遍不具备这样的素质。对许多人来说,似乎连四年选举前的思考都太具有挑战性了……

建构主义方法的一个关键方面是它改变了话语。当我们对现有事物提出批评时,我们是在当下的话语体系中运作的;我们对我们不喜欢的事物——比如过度军备或战争威胁——做出反应。我们总是在我们所批评的那些人的范式和话语中进行反驳。从根本上说,这是一种防御性战略。

相反,如果你争辩说:”为什么你们不采取以下建设性步骤来解决冲突,从而避免战争?——那么,你就设置了议程,塑造了话语,并将战争这一消极现象的鼓吹者置于防御状态。

这种建构主义方法的另一个至关重要的方面是,它提供了更多的正向思考。它可以通过移情和善意,让人们充满希望。它也并不意味着对任何人的攻击。

人们可以为某件事情付出尽可能长的时间,但如果只是与某人或某事作斗争,而不能较快地“获胜”,人类就会倾向于放弃;这时他们会说:“这是不可能的,我放弃了。”或者,他们继续奋斗,但越来越被愤怒甚至仇恨所驱使。

这可能是一个经典的心理学观察——但我依然想做一个基本的哲学补充:请记住,在我们尝试创造更美好的世界之前,我们不知道什么是可能的,什么是不可能的。这就是为什么传统主义者很容易用“哦,那不是不现实吗?你是不是太理想主义/太罗曼蒂克/天真了……?”

当人们说出这些话的时候,很有可能已经说了或做了一些令人兴奋的、新的,甚至可能是正确的事情。

建构主义的魅力在于,它邀请人们进行知识和实践方面的尝试。甘地最著名的一本书名为《我体验真理的故事》,这绝非巧合。

在下文中,我将做一个微不足道的尝试,践行现在所宣扬的理念。

民主

通常,民主被等同于“民有、民治、民享的政府”,美国总统亚伯拉罕·林肯曾对此进行过著名的阐述。他没有说民主,因为美国的任何基本文件中都没有这个词。美国最后一任驻苏联大使杰克·马特洛克(Jack Matlock)认为:

“事实是,美国不是民主国家。我们的任何基本文件中都没有这个词。《独立宣言》、《宪法》、效忠誓词(“效忠美利坚合众国国旗及其所代表的共和国”)以及每位联邦官员的就职宣誓中都没有这个词。

美国是一个共和国,目前由寡头政治控制。它也正变得越来越专制。政府三权分立是避免专制的必要条件,但这一原则已受到严重侵蚀。”

因此,民主、自由的西方世界领导的(甚至)不是一个民主国家。尽管如此——可能有些人对此感到惊讶——民主是西方社会的一个核心特征,通常被理解为代议制议会——即在自由选举中,公民投票选出代表他们利益的人进入由政党组成的议会,其中一些政党组成政府,一些政党组成反对党。

必须补充的是,民主需要合理的知识水平和可以自由获取的信息。例如,虽然印度经常被称为世界上最大的民主国家,但其26%的人口(2.87 亿人)仍然是文盲。

因此,这个“世界上最大的民主国家”也拥有世界上最多的不识字人口。相比之下,中国的文盲率约为 3%,而这个国家经常被西方称为独裁国家。

此外,在一个社会中,竞选公职的人是——或者说必须是——极其富有的人,才能支付他们的竞选费用,而且大公司向某些候选人提供数百万美元的捐款(大概不是出于利他主义),这样的社会就不属于民主的合理定义范围——尽管它们也可能不是独裁政权,有许多地方介于两者之间。

无论民主有什么优点,要区分宣传的民主和真正的民主并不那么容易。下文将对此进行详细介绍。

年轻人放弃议会民主了吗?

几十年前,当我还在读高中的时候,想要为社会的进步做出贡献,最自然、最美好的选择就是加入一个政党。今天却不是这样。我在世界各地学习和平研究的学生经常在课程结束、到了说再见的时候,问我是否能在他们的职业生涯中提供一些帮助。他们的职业梦想可能是为联合国、人权和环境工作,也可能是创办自己的以和平为主题的非政府组织,或者是成立自己的咨询公司来建设一个更美好的世界。

值得注意的是,这么多年来,只有一名学生问我对通过从政为和平与发展做贡献有何看法。

众所周知,如今人们主要通过民间社会以及社交媒体和抗议活动作为主要工具来参与社会问题。从大多数角度来看,这都是好事,为事实上的全球公民意识和行动带来了引人入胜的前景,但这也对由政党主导的旧式代议制民主造成了影响,因为他们仍然是该体系的主要决策者。

当我们谈论全球危机时,人们更多想到的是环境、身份问题或战争,而不是民主陷入危机。我认为,西方民主正处于根本性危机之中,原因至少有以下几点。

民主危机——部分要点

1. 国家正受到来自上层和下层的挑战

民主是与国家联系在一起的,是与我去投票的“我的国家”联系在一起的,而不是与国际社会联系在一起的。但是,由于来自下层和上层的压力,国家正在变得越来越弱。人们常说,全球性问题只能通过跨国家合作来解决,但这些问题都是在各种利益集团、地区协会和特设论坛上讨论的。在全球层面不存在民主决策机制。

2. 社会经济问题占主导地位

民主国家讨论的主要问题是经济问题,这有可能使民主沦为钱包政治。对经济的普遍关注意味着:(1) 在议会中进行的国家民主政治的功能是试图减轻正在肆虐的经济全球化的影响;(2)大部分社会问题和挑战都是通过经济参数和市场来解决的。或者说,是将几乎所有事物市场化/商品化。人们可能会质疑,在西方(新)自由主义社会中,市场是否比民主本身更具有决策者的作用。

3. 重物质轻人生价值

议会民主对资本主义经济的痴迷,使那些认为民主辩论也应涉及价值观、伦理以及正义与和平等概念的人感到无趣或不可行。在过去的二三十年里,民主政体逐步淘汰了各种知识主义和哲学——甚至包括对公民可能希望优先考虑的更美好未来社会愿景的公开讨论。

4. 时间跨度太短

当然,4年的视角——从一次选举到下一次选举——对于一个被复杂问题困扰的世界来说是远远不够的,解决这些问题需要我们所有人都有10-25年甚至更长的时间跨度。具有长远眼光的政治家根本不适合当今的西方议会,也很难在西方议会中找到。

5. 国家议会越来越不重要

由国家议会决定我们国家未来的事情越来越少。相反,影响我们和我们后代生活的真正具有约束力的决定是由更大、更遥远和以精英为基础的机构做出的,如华尔街、北约、欧盟、国际货币基金组织、银行、股市操纵者等。当这些机构做出决定后,各国议会就必须应对如何适应和调整全球框架条件的问题。

6. 全球经济和军事,但只有国家民主

我们社会中全球化程度最高的部门是企业界(例如,想想全球经济/市场、汇率、借贷、贸易、投资、金融、基础设施、全球采购等)和军方(想想武器生产、武器出口、基地、干涉主义、战争规划、理论、远程导弹、卫星、导航系统、反潜战、地区和全球战争以及核毁灭)。

这两个社会领域的精英具有全球思维。他们将世界视为一个可以运作的系统。虽然民族国家——他们自己的国家——对他们来说可能很重要,但这并不是他们在时间和空间上选择的主要视角。

因此,民主最大的问题或许在于,我们甚至没有一个能够与这两个强大的行为体相匹敌的全球民主的雏形。

7. 政治家必须在当选和讲真话之间做出选择

民主竞选中的候选人即使想说实话也做不到。任何候选人都必须承诺 “金色的森林”,只要我们投票给她或他的政党,我们未来的生活和消费就会变得多么美好。一个希望在政治上有所作为的人不能告诉投票的公民,我们还必须采取一些痛苦的措施,放弃一些活动,为子孙后代拯救地球。权力就是承诺——无论选举日之后是否兑现——因此,“金色”和“绿色森林”所剩无几。

在很大程度上,当涉及到世界的现状以及如何深入而广泛地解决环境问题时,民主在很大程度上是靠欺骗公民。

此外,在一个迫切需要复杂解决方案的世界里,民主是一个非常缓慢的决策过程。

8. 政治成为取代知识的公共关系

政治越来越多地被视为一种游戏、务实的导航、定位和交易。一般来说,改革、法律和政治立场被当作商品向公民推销。为此,你需要简短、有力的口号、新闻发言人和营销活动,而传统的公开对话和全社会的辩论则过于耗时,意味着精英和大众之间要会面(可能导致决策者改变在公民头上已经决定的事情)。

媒体的发展导致言辞越来越短。一切都必须在最多30秒的时间内表达出来,而注意力集中的时间却越来越短。要在30秒内表达精髓,否则就会失去观众!就公众教育和推进民主辩论而言,这是一个恶性循环。

这导致的是个人定位,而不是实质观点。作为一名政治家,你不必对中东或乌克兰等问题的复杂性有太多了解;能够站队——好人对坏人——变得更加重要。叙事往往简单得令人难以置信,而且经常是从华盛顿或布鲁塞尔等国外权力中心引进的。

因此,公民们看到的不是具有公共教育意义的对话(探讨问题)和辩论(允许各种观点交锋并得到论据支持),而是典型的体育比赛式的电视对抗: 我们的政策比你们的好!

谁的口才最好,谁的骗术更高明,谁的穿着更漂亮,谁就能“赢得”信任和选票。

由于现代通信和媒体的需求,在过去20年里,以知识为基础的政治决策的时间大大减少了,这对大量决策造成消极影响。

和所有硬币一样,这枚硬币也有第二面:企业及其品牌越来越多地融入政治。例如,《爱德曼2024年信任晴雨表》指出:

“政治是消费者最关心的问题,他们会从政治的角度看待品牌的行为:近八成的消费者认为品牌在做他们认为具有政治性或政治动机的事情。但消费者并不希望品牌回避政治。事实上,他们希望品牌能够解决气候变化、公平薪酬、技能再培训、公共卫生和多元化等关键问题,认为品牌的行动对社会进步至关重要。全球71%的受访者表示,在面临压力时,品牌必须在问题上表明立场,而只有12%的受访者表示,品牌必须避免表明立场”。(见https://www.edelman.com/trust/2024/trust-barometer/special-report-brand/brands-frontline-strengthening-trust-political-volatility)

最近,我们看到了企业如何表达/标榜自己是反俄罗斯和亲乌克兰的——而在以色列对巴勒斯坦人的种族灭绝问题上,他们表现得却非常低调。

总之,当西方社会的政治领域变得更加商业化和以市场/营销为导向时,经济领域——公司及其品牌——似乎变得更加政治化。这些长期趋势可能会进一步破坏民主的“经典”理论和实践。

与这枚硬币的两面密切相关的是金钱对政治的影响和腐蚀。在几乎所有的宪政民主国家,公民和企业都可以向竞选活动和政党捐款。这一点几乎无需赘述,在 2024 年秋季美国大选之后也是如此。格雷格·帕拉斯特(Greg Palast)在 2002 年出版的一本书《金钱能买到的最佳民主》(见https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Best_Democracy_Money_Can_Buy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greg_Palast)中简明扼要地阐述了这一点。

9. 政治是一种使命还是职业道路

曾经,政治的重点是促进特定的未来发展,政党之间的意识形态分歧显而易见。如今,政治更像是一种职业,一种职业选择;你在政界呆上几年,然后进入企业董事会或任何可能给你带来名利和资金的地方。

对某些社会问题充满热情的人不会选择从政,而是加入非政府组织、写博客、做社交媒体或成为企业家。正如上面提到的我的学生教我的那样。相反,政治吸引的是那些没有这种热情的人——也许除了由纳税人支付的个人特权、豪华轿车和频繁的头等舱旅行。别忘了,还有权力的吸引力。

这意味着政治不再吸引有远见的领导者,不再吸引能够激励年轻人的魅力型人格,不再吸引那些政治应该为他们而生的人。

除了上述标准例外——也有个别例外——大多数政治家都缺乏幽默(至少在台上)、魅力、热情、个性和远见——这使得民主活动和辩论在大多数时候都非常乏味。

10. 民主是投票而非选择

大多数人都正确地认为,民主的区别在于公民投票支持某个人、某个政党和法律,或者对政治精英设定的某些备选方案投赞成票或反对票(也称全民公决)。

但民主的基本理念并不是对我们不了解的人事先设定的问题进行投票。民主是——应该是——首先为制定议程做出贡献。

民主也不是只在两种选择中做出决定,比如:瑞士是否应该在国际争端中保持中立?瑞士未来是否应保持中立?是或否!理想情况下,民主应该是形成一个更广泛的范围(通过公众教育和辩论来塑造和改变),比如说,中立只是其中的一个选择/备选方案。

真正的民主是制定议程。它不是对某人预先确定的、或多或少有些狡猾的议程和候选人投赞成票或反对票。

也许你可以这样概括:民主不再是生活,而是表演。它已成为一种没有太多精神内涵的仪式。

11. 公民感到无法与决策者沟通

在西方世界,越来越多的公民表示,与高层决策者“沟通”极为困难。坦率地说,这也是我几十年来的亲身经历。

与几十年前相比,这些高层决策者似乎也觉得与选民直接对话不那么重要了。以前,把答复装在信封里寄给公民是一种责任,而现在,他们给代表或部长写信时,连电子邮件或其他回复都不再能收到。政治体制有自己的看门人,即使你向政治家寄去建设性的建议或研究报告,指望得到回复、确认收到或一句感谢的话也是天真的。顺便说一句,与媒体界沟通的尝试也是如此。

总之,我很难不同意甘地近百年前的激进批评:

莫罕达斯·甘地的名言:我对民主的见解是,最弱者应该与最强者有同样的机会。目前世界上没有一个国家表现出对弱者的尊重,而是高人一等。今天运行的西方民主,乃是稀释过的法西斯。真正的民主不能由坐在中心的二十个男人来操作。真正的民主必须由每个村民自下而上来进行。

法国存在主义哲学家让·保罗·萨特(Jean-Paul Sartre,1905~1980年)在他最后的一次访谈中说,公民的每一次投票都是在放弃权力。这句话指出了代议制民主与直接民主之间的基本经典区别。在前者中,选民将权力委托给其他人,而后者则说服/教育选民照顾公民的利益。

我们知道,这通常会导致虚假承诺和对政治的严重失望。在第二种情况下,公民将问题掌握在自己手中——当然,这也有其弊端,并包含一系列其他问题,其中最重要的是如何组织起来。尽管如此,如果没有一个充满活力、积极主动、受过良好教育的公民群体,真正的民主是不可能实现的。

最不坏但远不够好

总之,虽然民主也许仍然是最不坏的制度,但我们不应将其等同于民主足够好。

将西方民主制度与专制制度进行长期比较并不能证明其质量或完美性。每一种好的制度都可以而且应该加以改进——也就是说,我们需要将民主民主化,将其简化一些。至少其中的某些要素应该提升到更高的层次——将民主全球化,使全球及其过时的威斯特伐利亚的国家(民族)决策程序民主化。

其次,西方民主国家必须接受并尊重非西方的民主模式,这些模式不一定是不民主或反民主的,也不一定应该受到反对。任何制度都不应成为普世制度。在民主治理方面也是如此,在多样性中求得统一对我们都有好处。

在这个问题上的自满情绪很容易使西方迅速走向专制主义,而西方却坚称自己是专制主义的解毒剂。这些指标已经在蓬勃发展…..

联合国改革与全球治理

本联合国是世界上唯一最重要的和平愿景组织,将于2025年10月24日迎来80周岁生日。自1986年成立以来,瑞典跨国和平与未来研究基金会(TFF)一直致力于宣传《联合国宪章》第一条,即 “应以和平方法实现和平”。

这是甘地的启示。正如他所说,“手段就含在目标之中”。不能用破坏性的手段来实现建设性的目标。

遗憾的是,人们经常指责联合国太昂贵、太官僚、太无效、太腐败,或者太这太那。

以下是笔者认为这种说法缺乏理智——也很危险——的原因:

首先,正如联合国首任秘书长、挪威人特里格夫·赖伊所言,联合国永远不会比其成员国希望的更强大或更好。可悲的是,这些国家的民族主义仍然远远大于全球主义。

赖伊的话仍然一针见血。简单地说,是会员国(有些会员国比其他会员国更甚)在国际上的行为和在联合国的政策削弱了这一世界组织及其准则,削弱了其权力和作用,并使其行动边缘化。

其次,那些说世界完全可以关闭“过时的”联合国的人,只是没有考虑到联合国的预算是多么少,以及世界上的军事—工业—-媒体—学术联合体(MIMACs)对联合国及其准则的破坏力有多强,要想用如此少的资金让世界变得更美好是多么不可能。

2024年联合国经常预算为35.9亿美元,比上一年预算增加近3亿美元。该预算支持联合国秘书处的核心职能,包括为各种行动提供资金,其中包括建设和平的努力。其所有成员机构(如世卫组织、儿基会等)的年度总支出为500亿至600亿美元。

现在,将其与全球军国主义的成本进行比较:今天,联合国会员国的军费开支是有史以来全球最高的,达到24000亿美元。

这意味着,世界军费开支是联合国正常基本预算(包括维和预算)的666倍,是联合国及其下属组织所做的所有好事的总和的40倍。

如果军国主义纵火狂拥有多出40倍的资源来放火,你还能预防或扑灭什么火灾呢?诚然,这是一个反问句,但它提出了一个具有重要现实意义的问题: 这个世界的优先事项如果不是倒行逆施,也是荒谬可笑的,而人们却几乎没有讨论过这些优先事项。

大多数人似乎都认为,这种对人类资源难以想象的浪费是为所谓的“安全”所付出的代价。然而,就在2024年底写这篇文章的时候,战争已经迫在眉睫,至少在欧洲是这样,全世界几乎所有国家都计划增加军费开支。

第三,无论有意还是无意,这些批评者都隐含着这样的意思: 我们宁愿让美帝国(和其他一些国家)管理世界,也不愿让联合国管理世界。这是一种危险的思维方式,它完全破坏了国际法和极其重要的《联合国宪章》——世界各国政府签署的最具甘地风格的文件。

值得指出的是,在全球和联合国历史的这一特殊时刻,鉴于美国总统唐纳德·特朗普对联合国的态度以及他任命来管理美国联合国政策的人,我们有理由对联合国的未来极为担忧。请参阅塔利夫·迪恩(Thalif Deen)2024年11月29日在国际新闻通讯社(Inter Press Sevice)发表的《美国特使抨击联合国腐败并威胁削减资金》(“US Envoy-in-Waiting Blasts UN as Corrupt – & Threatens Funding Cut”)。

现在绝对不是批评“联合国”的时候,至少,不能不同时提出有远见的改革建议和全球治理建议。

毫无疑问,拯救人类和我们共同的全球未来,需要通过联合国及其《宪章》准则——不是唯一的变革者,而是最核心的变革者。

当然,联合国必须改革。但正如我们在下文中所述,各国政府和人民,包括媒体和政治家,更需要改革他们对联合国的态度和政策。

当我们对这个问题进行更深入的思考时,就会发现它是一个更大的进程的一部分,即超越国家和地区层面的决策民主化,并开始以全新的、适应未来的方式思考全球治理。

如果人类发展出比联合国更好的东西,我们可能会转而使用它,并关闭我们今天所知的联合国。但在此之前,我们一刻也不会停歇。

这个新机构也不会设在对联合国伤害最大的会员国。但在那之前,让我们让现在的联合国变得更加强大,使其最终能够实现其初衷:为共同利益服务,废除战争——通过和平——文明的手段实现和平,从而将使用集体暴力作为绝对的最后手段。

“我们,人民”必须自下而上地努力实现这一点,因为“他们,政府”一直在违反《联合国宪章》中极为重要的第一条和整个规范框架。而且还在继续这样做!

以下是关于全球民主和强大联合国的一系列建议。有些人肯定会认为这些建议“不切实际”或“罗曼蒂克”。当有人建议废除奴隶制时,当欧洲人抗议在20世纪80年代部署中程核导弹并最终将其销毁时,当有人预言苏联和华沙条约组织将很快解体并推倒柏林墙时……或者当人们开始发起减少吸烟的运动时,许多人也是这么想的,也是这么说的。

让我们首先关注与联合国有关的民主问题。值得强调的是,民主和全球体系(我们避免称其为“国际社会”,因为“国家间”是一个过时的术语,美国只将其滥用于西方世界,而在西方通过猖獗的军国主义和对抗政策自我孤立的时代,“社会”事实上并不存在)存在许多问题。

首先,“民主”本身是一个复杂的术语,哲学家称之为“有争议的概念”。但这里并不是从哲学角度论述什么是民主的地方。

其次,民主虽然可能是迄今为止最不坏的理论,但却被认为是“伪”的、无效的,并被西方世界(和日本)的一些权力精英系统地规避,这该怎么办?

第三,它是一个带有西方偏见的概念,通常只意味着多党制、法律面前人人平等、言论自由、自由选举以及议会和新闻自由等一系列社会机构。因此,许多人认为苏联是独裁国家,因为它只有一个政党,而美国是民主国家,因为它有两个政党。然而,真正的民主还在于一种特殊的政治文化,它自然而然地寻求吸纳非多数派。

第四,虽然民主化是可取的,但我们如何一方面避免政治-文化帝国主义,将一个深具西方色彩的定义和概念/理论普遍化,另一方面避免文化例外主义,即允许任何制度或独裁者根据当地的价值观和解释将一个社会称为民主社会?

第五,在国际层面没有民主,没有类似于民族国家的机构;因此,我们将不得不把民主建立在唯一一个面向全球的机构之上,该机构可以朝着超国家层面的多元文化民主机构的方向进行改革:联合国。

但是,联合国本身必须民主化,它必须尽快体现民主化的世界秩序。现在是认真对待“我们人民”的时候了,也是研究哪些人民应该在世界事务和联合国事务中拥有发言权的时候了。当然,这里的关键词是人民主权,即系统地承认主权属于世界人民和全球公民的原则。

第六,正如甘地所指出的,立足于倒退的民主政体,通过暴力(军队、国家镇压、监狱、法院、死刑等)来维持其秩序。除了哥斯达黎加、冰岛等例外,也许还有其他一些国家,所有民主国家都从武器出口中获利/受益,而且它们往往支持政治干预主义和核活动。换句话说,西方民主和西方军国主义深深地交织在一起——尽管根据经验,民主国家通常不会与它们认为民主的其他国家进行(军事)战争——但这并不排除可以进行经济战争。

第七,大多数民主国家对社会与自然关系的态度也是如此。现代民主国家与资本主义的全面、普遍缠绕导致了对环境的破坏。民主世界,而不是共产主义或独裁政权,砍伐雨林,扼杀物种、语言和“原始”文化,几个世纪以来一直如此。

幸运的是,环境和社会经济(不良)发展比任何其他问题都更有说服力,可以作为重组现有国际组织、创建新组织、改变政府政治的含义以涵盖地区和全球层面的论据。

这就是生态政治学的意义所在。

今天,联合国完全无法有效应对这一文明挑战。事实上,可持续发展这一概念已经深入人心,这说明有必要在联合国内部建立一个全新的组织。此外,环境议程似乎比其他议程更能反映全人类的共同利益。

1991 年,瑞典跨国和平与未来研究基金会(TFF)理事会发表了题为 “未来的联合国”的TFF 声明。“我们,人民”和各国政府可以做些什么来帮助联合国自助。

在声明中,我们建议在维和、发展、环境以及联合国本身和国际社会的民主化方面进行大刀阔斧的改革。

以下是其中的一些建议——进行了必要的修订、重新表述和更新:

● 联合国安理会应改革,否决权应受到限制

安理会五个常任理事国的影响力异常强大,这与任何全球民主的概念都是不相容的。同样,安理会的组成也不能反映全球社会及其动态变化。

也许不应该有安理会常任理事国——当然也不应该有那些武器装备最先进、最善于作战和拥有核武器的国家?也许应该设立一个没有常任理事国的安全理事会,但安理会成员每隔一段时间就更换一次,这样,随着时间的推移,所有会员国都能轮流担任安全理事会理事国?

安理会常任理事国的否决权应该消失,或者仅限于在某些领域和情况下使用。安理会可以用常任理事国和当选理事国的双重多数来取代否决权。无论我们倾向于什么,我们都不能再忽视对安全理事会、其成员资格标准和运作方式进行全面改革的必要性。

我们认为,逐步淡化否决权不仅是可取的,而且是可能的。此外,今后必须加强秘书长和新的领导机构以及大会的付酬、和平和民主的权力,而不是依赖否决权的消极权力。因此:

● 联合国需要一个更强有力的秘书长和一个新的领导机构

事实上,关于秘书长职能的规定(尤其是第九十九条和第一百条)是《宪章》对超国家性做出的唯一让步。然而,要满足《宪章》对秘书长提出的所有要求以及自那时以来形成的惯例,更不用说所要求的个人素质,就需要有超人的人格。

现在,高层的集体领导是必要的。它可以由五人组成:秘书长本人,负责和平与安全、经济、环境和社会事务以及行政与管理的三名副手。第五位是负责与公众、非政府组织和私营部门关系的新副手。

● 联合国大会应得到振兴

在提高对全球问题的政治认识方面,联合国大会(GA)今后可能会发挥最重要的作用。大会可以发起特别会议,向更广泛的受众宣传事实、评估和紧迫性。

大会的立法权必须具有约束力,并与同时决定要采取的行动(及其资金来源)挂钩。这必须是一个协商一致的决定,而且需要有具有法律约束力的公约。1950 年11月的“联合一致共策和平”决议规定,在安全理事会无法解决破坏和平或侵略行为的情况下,联大将举行会议,建议采取集体措施。

● 联合国需要新的支持者

联合国实际上就是各国政府的联合。毫无疑问,一些政府是事实上的 “非人民组织”(NPO),而许多民间社会组织,或所谓的非政府组织,是真正的人民组织(PO),但无法进入“我们人民”的联合国及其各种论坛。(令人遗憾的是,还有越来越多的非政府组织,由于资金和领导层的原因,可以更准确地称为“近政府组织”)。

因此,应当以各种方式引入新的参与者,并保证他们真正独立于国家和政府。我们建议将其分为以下几类:(1) 国际组织;(2)代表事业或世界性问题而非政党或国家的跨国组织,如各种运动和倡议;(3) 少数民族和土著人民;(4) 难民和流离失所者;(5) 18 岁以下的儿童和青年;(6) 跨国公司。

● 在所有这些非政府组织和所有联合国机构之间建立联系和磋商程序——并利用听证会

咨商地位、直接参与各委员会和机构的工作、在整个联合国系统内建立详尽的听证制度、听取分析和建议并邀请发言、委托实况调查、与这些组织一起开展研究等,所有这些措施都体现了如何将急需的民主化与收集知识和创新观点结合起来,哪怕是循序渐进地实施。

有效地利用非政府资源将极大地丰富联合国,并将其转变为一个更有活力的机构,被全世界的公民视为与他们息息相关。

● 应建立公民大会或第二大会

我们只能对经常提出的第二议院或“平行结构”表示同情。也许明智的做法是逐步引入,并首先确定它应具有哪些选区(见上文)以及如何选举这些选区。

● 直接选举联合国代表

如今,外交部任命本国的联合国大使和工作人员。公民没有机会影响谁将代表他们——“我们,人民”。

这给人一种距离感。然而,《联合国宪章》中没有任何条款禁止任何会员国通过直接选举任命自己的代表,但要求他们这样做在今天几乎是不可能的。

对于大会以外的其他机构,如各机构和拟议的非政府行为者第二会议厅,公民应有机会投票选举候选人。

● 应有效地“推销”联合国这一全球媒体

或多或少重要的新闻——与体育、娱乐、辩论等相结合——通过传统方式或社交媒体全天候传播到世界各地。但联合国却没有类似的结构,没有商业广告、教育节目、辩论、娱乐,没有宣传活动,没有报道,也没有每天向我们传播的辩论和分析。

联合国太受西方主流媒体的摆布了。

联合国的大多数文件,甚至是公共信息材料,对普通公民来说,似乎没有任何刺激性。我们生活在一个全球化、数字化、多渠道传播的时代,联合国必须发展创造性的媒体能力和世界范围的日常存在,并找到足够的资金进入我们的客厅——至少达到公共服务广播公司、CNN、BBC 或 CGTN 的程度。联合国全球传播部做了很多好事,但它需要资源才能达到上述媒体的水平,才能在未来脱颖而出,成为世界新闻、事件、趋势和讨论的首选来源。见(https://www.un.org/en/department-global-communications/news-media)

现在,会员国政府可以做些什么?

● 会员国应将联合国准则和长期目标纳入国家决策,并放弃部分主权

显然,民族国家正在失去对跨国行动者和环境的影响力。各国政府应认识到,虽然他们现在放弃了一些主权,但日后他们将从合作、尽早解决问题以及秩序而非混乱中获益。顾及他人,放眼全球,以新的方式开展合作,是所有人生存的必要条件。

成员国政府的承诺可以从两个角度来看:可以鼓励它们改进政策,确保与它们在纽约支持的决定保持一致。还可以采用一种更为严厉的机制,即暂停那些一再违反《联合国宪章》准则、决议和其他决定的成员国的资格。暂停期限应取决于其违反行为的严重程度。尽管如此,永久性地将任何成员国排除在外可能并不明智。

● 会员国应制定真正的自卫和新的安全政策

任何国家采取纯粹防御性的军事和/或民事态势和理论,都会自动解决许多严重问题,否则这些问题就会被推卸给秘书长或通过战场上赤裸裸的武力来解决。